The African Theatre of the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

comprises campaigns in

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

instigated by the German and Ottoman empires, local rebellions against European colonial rule and

Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

campaigns against the

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

colonies of

Kamerun

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern p ...

,

Togoland

Togoland was a German Empire protectorate in West Africa from 1884 to 1914, encompassing what is now the nation of Togo and most of what is now the Volta Region of Ghana, approximately 90,400 km2 (29,867 sq mi) in size. During the period kno ...

,

German South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

and

German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; german: Deutsch-Ostafrika) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mozam ...

. The campaigns were fought by German , local resistance movements and forces of the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

,

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

and

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

.

Background

Strategic context

German colonies in Africa had been acquired in the 1880s and were not well defended. They were also surrounded by territories controlled by

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

,

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

and

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

. Colonial military forces in Africa were relatively small, poorly equipped and had been created to maintain internal order, rather than conduct military operations against other colonial forces. The

Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergence ...

of 1884 had provided for European colonies in Africa to be

neutral

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

if war broke out in Europe; in 1914 none of the European powers had plans to challenge their opponents for control of overseas colonies. When news of the outbreak of war reached European colonialists in Africa, it was met by little of the enthusiasm seen in the capital cities of the states which maintained colonies. An editorial in the ''

East African Standard

''The Standard'' is one of the largest newspapers in Kenya with a 48% market share. It is the oldest newspaper in the country and is owned by The Standard Group, which also runs the Kenya Television Network (KTN), Radio Maisha, ''The Nairobian ...

'' on 22 August argued that

Europeans in Africa should not fight each other but instead collaborate to maintain the repression of the

indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

population. War was against the interest of the white colonialists because they were small in number, many of the European conquests were recent, unstable and operated through existing local structures of power; the organisation of African economic potential for European profit had only recently begun.

In Britain, an Offensive sub-committee of the

Committee of Imperial Defence

The Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ''ad hoc'' part of the Government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of the Second World War. It was responsible for research, and som ...

was appointed on 5 August and established a principle that

command of the sea

Command of the sea (also called control of the sea or sea control) is a naval military concept regarding the strength of a particular navy to a specific naval area it controls. A navy has command of the sea when it is so strong that its rivals ...

s was to be ensured and that objectives were considered only if they could be attained with local forces and if the objective assisted the priority of maintaining British sea communications, as

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

garrisons abroad were returned to Europe in an "Imperial Concentration". Attacks on German coaling stations and wireless stations were considered to be important to clear the seas of Imperial German Navy

commerce raiders

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than enga ...

. The objectives were at

Luderitz Bay,

Windhoek

Windhoek (, , ) is the capital and largest city of Namibia. It is located in central Namibia in the Khomas Highland plateau area, at around above sea level, almost exactly at the country's geographical centre. The population of Windhoek in 20 ...

,

Duala and

Dar-es-Salaam

Dar es Salaam (; from ar, دَار السَّلَام, Dâr es-Selâm, lit=Abode of Peace) or commonly known as Dar, is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over ...

in Africa and a German wireless station in Togoland, next to the British colony of Gold Coast in the

Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez in Gabon, north and west to Cape Palmas in Liberia. The intersection of the Equator and Prime Meridian (zero degrees latitude and longitude) is in the ...

, which were considered vulnerable to attack by local or allied forces and in the Far East, which led to the

Siege of Tsingtao

The siege of Tsingtao (or Tsingtau) was the attack on the German port of Tsingtao (now Qingdao) in China during World War I by Japan and the United Kingdom. The siege was waged against Imperial Germany between 27 August and 7 November 1914. Th ...

.

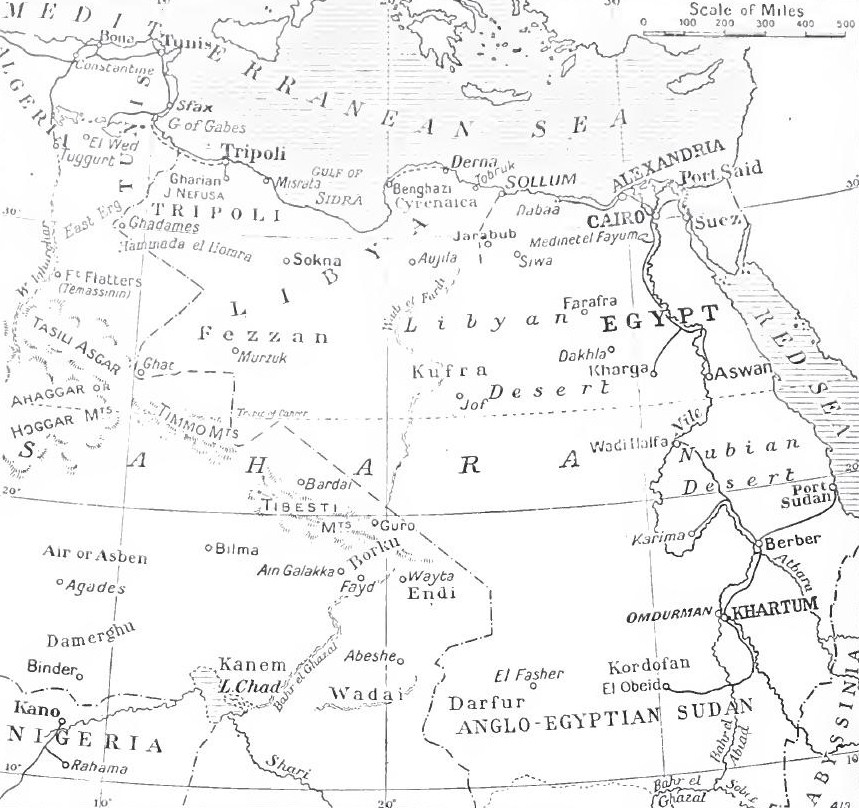

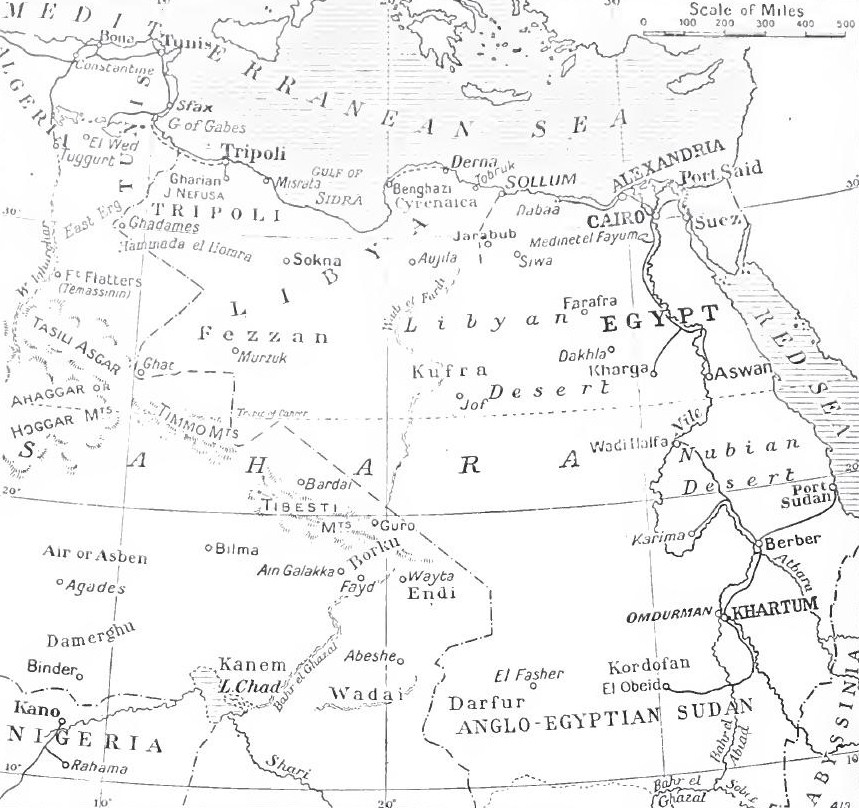

North Africa

Zaian War, 1914–1921

Attempts were made by the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

and the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

to influence conditions in the French colonies by intriguing with the potentates who had been ousted by the French. Spanish authorities in the region informally tolerated the distribution of propaganda and money but thwarted a German plot to smuggle 5,000 rifles and 500,000 bullets through Spain. The maintained several agents in North Africa but had only two in Morocco. The Zaian War was fought between France and the

Zaian confederation of

Berber people

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber flag, Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, p ...

in

French Morocco

The French protectorate in Morocco (french: Protectorat français au Maroc; ar, الحماية الفرنسية في المغرب), also known as French Morocco, was the period of French colonial rule in Morocco between 1912 to 1956. The prote ...

between 1914 and 1921. Morocco had become a French protectorate in 1912 and the

French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed For ...

extended French influence eastwards through the

Middle Atlas

The Middle Atlas (Amazigh: ⴰⵟⵍⴰⵙ ⴰⵏⴰⵎⵎⴰⵙ, ''Atlas Anammas'', Arabic: الأطلس المتوسط, ''al-Aṭlas al-Mutawassiṭ'') is a mountain range in Morocco. It is part of the Atlas mountain range, a mountainous region ...

mountains towards

French Algeria

French Algeria (french: Alger to 1839, then afterwards; unofficially , ar, الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of French colonisation of Algeria. French rule in the region began in 1830 with the ...

. The Zaians, led by

Mouha ou Hammou Zayani

Mouha Ou Hammou Zayani, by his full name: Mohammed ou Hammou ben Akka ben Ahmed, also known as Moha Ou Hamou al-Harkati Zayani (c.1863 – 27 March 1921) was a Moroccan Berber military figure and tribal leader who played an important role in ...

quickly lost the towns of

Taza and

Khénifra

Khenifra ( Berber: ''Xnifṛa'', ⵅⵏⵉⴼⵕⴰ, ar, خنيفرة) is a city in northern central Morocco, surrounded by the Atlas Mountains and located on the Oum Er-Rbia River. National Highway 8 also goes through the town. The population, a ...

but managed to inflict many casualties on the French, who responded by establishing ,

combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme vio ...

formations of regular and irregular infantry, cavalry and artillery. By 1914 the French had in Morocco but two-thirds were withdrawn from 1914 to 1915 for service in France and at the

Battle of El Herri

The Battle of El Herri (also known as Elhri) was fought between France and the Berber people, Berber Zaian Confederation on 13 November 1914. It took place at the small settlement of El Herri, near Khénifra in the French protectorate in Morocc ...

(13 November 1914) more than soldiers were killed.

Hubert Lyautey

Louis Hubert Gonzalve Lyautey (17 November 1854 – 27 July 1934) was a French Army general and colonial administrator. After serving in Indochina and Madagascar, he became the first French Resident-General in Morocco from 1912 to 1925. Early in ...

, the governor, reorganised his forces and pursued a forward policy rather than passive defence. The French regained most of the lost territory, despite intelligence and financial support from the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

to the Zaian Confederation and raids which caused losses to the French when already short of manpower.

Senussi campaign, 1915–1917

Coastal campaign, 1915–1916

On 6 November, the German submarine

''U–35'' torpedoed and sank a steamer, , in the Bay of

Sollum

Sallum ( ar, السلوم, translit=as-Sallūm various transliterations include ''El Salloum'', ''As Sallum'' or ''Sollum'') is a harbourside village or town in Egypt. It is along the Egypt/Libyan short north–south aligned coast of the Mediterra ...

. ''U-35'' surfaced, sank the coastguard gunboat ''Abbas'' and badly damaged ''Nur el Bahr'' with its deck gun. On 14 November the Senussi attacked an Egyptian position at Sollum and on the night of 17 November, a party of Senussi fired into Sollum as another party cut the coast telegraph line. Next night a monastery at

Sidi Barrani

Sidi Barrani ( ar, سيدي براني ) is a town in Egypt, near the Mediterranean Sea, about

east of the Egypt–Libya border, and around from Tobruk, Libya.

Named after Sidi es-Saadi el Barrani, a Senussi sheikh who was a head of ...

, beyond Sollum, was occupied by 300 and on the night of 19 November, a coastguard was killed. An Egyptian post was attacked east of Sollum on 20 November. The British withdrew from Sollum to

Mersa Matruh

Mersa Matruh ( ar, مرسى مطروح, translit=Marsā Maṭrūḥ, ), also transliterated as ''Marsa Matruh'', is a port in Egypt and the capital of Matrouh Governorate. It is located west of Alexandria and east of Sallum on the main highway ...

, further east, which had better facilities for a base and the

Western Frontier Force

The Western Frontier Force was raised from British Empire troops during the Senussi Campaign from November 1915 to February 1917, under the command of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF). Orders for the formation of the force were issued on ...

(Major-General A. Wallace) was created. On 11 December, a British column sent to Duwwar Hussein was attacked along the Matruh–Sollum track and in the Affair of Wadi Senba, drove the Senussi out of the wadi. The reconnaissance continued and on 13 December at Wadi Hasheifiat, the British were attacked again and held up until artillery came into action in the afternoon and forced the Senussi to retreat.

The British returned to Matruh until 25 December and then made a night advance to surprise the Senussi. At the Affair of Wadi Majid, the Senussi were defeated but were able to withdraw to the west. Air reconnaissance found more Senussi encampments in the vicinity of Matruh at Halazin, which was attacked on 23 January, in the Affair of Halazin. The Senussi fell back skilfully and then attempted to envelop the British flanks. The British were pushed back on the flanks as the centre advanced and defeated the main body of Senussi, who were again able to withdraw. In February 1916, the Western Frontier Force was reinforced and a British column was sent west along the coast to re-capture

Sollum

Sallum ( ar, السلوم, translit=as-Sallūm various transliterations include ''El Salloum'', ''As Sallum'' or ''Sollum'') is a harbourside village or town in Egypt. It is along the Egypt/Libyan short north–south aligned coast of the Mediterra ...

. Air reconnaissance discovered a Senussi encampment at Agagia, which was attacked in the

action of Agagia

The Action of Agagia (also Agagiya, Aqqaqia or Aqaqia) took place east of Sidi Barrani in Egypt on 26 February 1916, during the Senussi Campaign between German and Ottoman-instigated Senussi forces and the British army in Egypt. On 11 December ...

on 26 February. The Senussi were defeated and then intercepted by the

Dorset Yeomanry

The Queen's Own Dorset Yeomanry was a yeomanry regiment of the British Army founded in 1794 as the Dorsetshire Regiment of Volunteer Yeomanry Cavalry in response to the growing threat of invasion during the Napoleonic wars. It gained its first ro ...

as they withdrew; the Yeomanry charged across open ground swept by machine-gun and rifle fire. The British lost half their horses and men but prevented the Senussi from slipping away.

Jafar Pasha, the commander of the Senussi forces on the coast, was captured and Sollum was re-occupied by British forces on 14 March 1916, which concluded the coastal campaign.

Band of Oases campaign, 1916–1917

On 11 February 1916

Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi, leader of the

Senussi

The Senusiyya, Senussi or Sanusi ( ar, السنوسية ''as-Sanūssiyya'') are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi ( ar, السنوسي ...

order in

Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

, occupied

Bahariya Oasis

El-Wahat el-Bahariya or el-Bahariya ( ar, الواحات البحرية "''El-Wāḥāt El-Baḥrīya''", "the Northern Oases"); is a Depression (geology), depression and a naturally rich oasis in the Western Desert (Egypt), Western Desert of Egypt ...

in

Giza

Giza (; sometimes spelled ''Gizah'' arz, الجيزة ' ) is the second-largest city in Egypt after Cairo and fourth-largest city in Africa after Kinshasa, Lagos and Cairo. It is the capital of Giza Governorate with a total population of 9.2 ...

, which was then attacked by British

Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

bombers.

Farafra Oasis

The Farafra depression ( ar, واحة الفرافرة, ) is a geological depression, the second biggest by size in Western Egypt and the smallest by population, near latitude 27.06° north and longitude 27.97° east. It is in the large Wester ...

was occupied at the same time and then the Senussi moved on to

Dakhla Oasis

Dakhla Oasis (Egyptian Arabic: , , "''the inner oasis"''), is one of the seven oases of Egypt's Western Desert. Dakhla Oasis lies in the New Valley Governorate, 350 km (220 mi.) from the Nile and between the oases of Farafra and Khar ...

on 27 February. The British responded by forming the Southern Force at

Beni Suef

Beni Suef ( ar, بني سويف, Baniswēf the capital city of the Beni Suef Governorate in Egypt. Beni Suef is the location of Beni Suef University. An important agricultural trade centre on the west bank of the Nile River, the city is located 11 ...

. Egyptian officials at

Kharga Oasis

The Kharga Oasis (Arabic: , ) ; Coptic: ( "Oasis of Hib", "Oasis of Psoi") is the southernmost of Egypt's five western oases. It is located in the Western Desert, about 200 km (125 miles) to the west of the Nile valley. "Kharga" or ...

were withdrawn and the oasis was occupied by the Senussi until they withdrew without being attacked. The British reoccupied the oasis on 15 April and began to extend the light railway terminus at Kharga to the

Moghara Oasis. The mainly Australian

Imperial Camel Corps

The Imperial Camel Corps Brigade (ICCB) was a camel-mounted infantry brigade that the British Empire raised in December 1916 during the First World War for service in the Middle East.

From a small beginning the unit eventually grew to a brigad ...

patrolled on camels and in light

Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. The company sells automobi ...

cars to cut off the Senussi from the

Nile Valley

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest rive ...

. Preparations to attack Bahariya Oasis were detected by the Senussi garrison, which withdrew to Siwa in early October. The Southern Force attacked the Senussi in the Affairs in the Dakhla Oasis , after which the Senussi retreated to their base at

Siwa.

In January 1917, a British column including the Light Armoured Car Brigade with

Rolls-Royce Armoured Cars and three Light Car Patrols was dispatched to Siwa. On 3 February the armoured cars surprised and engaged the Senussi at

Girba

Djerba (; ar, جربة, Jirba, ; it, Meninge, Girba), also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is a Tunisian island and the largest island of North Africa at , in the Gulf of Gabès, off the coast of Tunisia. It had a population of 139,544 a ...

, who retreated overnight. Siwa was entered on 4 February without opposition but a British ambush party at the Munassib Pass was foiled, when the escarpment was found to be too steep for the armoured cars. The light cars managed to descend the escarpment and captured a convoy on 4 February. Next day the Senussi from Girba were intercepted but managed to establish a post the cars were unable to reach and then warned the rest of the Senussi. The British force returned to

Matruh on 8 February and Sayyid Ahmed withdrew to

Jaghbub

Jaghbub ( ar, الجغبوب) is a remote desert village in the Al Jaghbub Oasis in the eastern Libyan Desert. It is actually closer to the Egyptian town of Siwa than to any Libyan town of note. The oasis is located in Butnan District and was th ...

. Negotiations between Sayed Idris and the Anglo-Italians which had begun in late January were galvanised by news of the Senussi defeat at Siwa. In the

accords of Akramah, Idris accepted the British terms on 12 April and those of Italy on 14 April.

Volta-Bani War, 1915–1917

The Volta-Bani War was an anti-colonial rebellion that took place in parts of

French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now Burki ...

(now

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso (, ; , ff, 𞤄𞤵𞤪𞤳𞤭𞤲𞤢 𞤊𞤢𞤧𞤮, italic=no) is a landlocked country in West Africa with an area of , bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the ...

and

Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali ...

) between 1915 and 1917. It was a war between an indigenous African army, a heterogeneous coalition of peoples against the French Army. At its height in 1916, the indigenous forces mustered from 15,000–20,000 men and fought on several fronts. After about a year and several setbacks, the French army defeated the insurgents and jailed or executed their leaders but resistance continued until 1917.

Darfur Expedition, 1916

On 1 March 1916 hostilities began between the Sudanese government and the

Sultanate of Darfur

The Sultanate of Darfur was a pre-colonial state in present-day Sudan. It existed from 1603 to October 24, 1874, when it fell to the Sudanese warlord Rabih az-Zubayr and again from 1898 to 1916, when it was conquered by the British and integr ...

. The Anglo-Egyptian Darfur Expedition was conducted to forestall an imagined invasion of

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ar, السودان الإنجليزي المصري ') was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt in the Sudans region of northern Africa between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day ...

and the

Sultanate of Egypt

The Sultanate of Egypt () was the short-lived protectorate that the United Kingdom imposed over Egypt between 1914 and 1922.

History

Soon after the start of the First World War, Khedive Abbas II of Egypt was removed from power by the British ...

by the Darfurian leader,

Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

Ali Dinar

Ali Dinar ( ar, علي دينار; 1856 – November 6, 1916) was a Sultan of the Sultanate of Darfur and ruler from the Keira dynasty.

In 1898, with the decline of the Mahdists, he managed to regain Darfur's independence.

A rebellion ...

, which was believed to have been synchronised with a Senussi advance into Egypt from the west. The

Sirdar

The rank of Sirdar ( ar, سردار) – a variant of Sardar – was assigned to the British Commander-in-Chief of the British-controlled Egyptian Army in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Sirdar resided at the Sirdaria, a three-blo ...

(commander) of the

Egyptian Army organised a force of men at

Rahad

Ar-Rahad ( ar, ٱلـرَّهَـد, "The Water-shrine") is a city located in the state of North Kordofan, Sudan, at an altitude of above sea level. It is about away from the capital, Khartoum. It is a major railway station linking East and Cent ...

, a railhead east of the Darfur frontier. On 16 March, the force crossed the frontier mounted in lorries from a forward base established at

Nahud

En Nahud is a town in the desert of central Sudan. Formerly located within the Sudanese political division of West Kurdufan, it is now part of the country's North Kurdufan state.

History

In 2021, the Darsaya gold mine in the town collapsed, ...

, from the border, with the support of four aircraft. By May the force was close to the Darfur capital of

El Fasher

Al Fashir, Al-Fashir or El Fasher ( ar, الفاشر) is the capital city of North Darfur, Sudan. It is a large town in the Darfur region of northwestern Sudan, northeast of Nyala, Sudan.

"Al-Fashir" (description)

''Encyclopædia Brit ...

. At the Affair of Beringia on 22 May, the Fur Army was defeated and the Anglo-Egyptian force captured the capital the next day. Dinar and had left before their arrival and as they moved south, were bombed from the air.

French troops in Chad who had returned from the

Kamerun Campaign prevented a Darfurian withdrawal westwards. Dinar withdrew into the Marra Mountains south of El Fasher and sent envoys to discuss terms but the British believed he was prevaricating and ended the talks on 1 August. Internal dissension reduced the force with Dinar to men; Anglo-Egyptian outposts were pushed out from El Fasher to the west and southwest after the August rains. A skirmish took place at Dibbis on 13 October and Dinar opened negotiations but was again suspected of bad faith. Dinar fled southwest to Gyuba and a small force was sent in pursuit. At dawn on 6 November, the Anglo-Egyptians attacked in the Affair of Gyuba and Dinar's remaining followers scattered. The body of the Sultan was found from the camp. After the expedition, Darfur was incorporated into Sudan.

Kaocen revolt, 1916–1917

Ag Mohammed Wau Teguidda Kaocen

Kaocen Ag Geda (1880–1919) (also known as Kaocen, Kaosen, Kawsen) was a Tuareg noble and clan leader. Born in 1880 near wadi Tamazlaght Aïr (modern Niger), Kaocen from tribe of Ikazkazan berber, a subset of the Kel Owey confederation. He ...

(1880–1919), the

Amenokal Amenukal ( Berber: ⵎⵏⴾⵍ, ⴰⵎⵏⵓⴽⴰⵍ) is a title for the highest Tuareg traditional chiefs; the paramount confederation leader.

History

Prior to the colonial period in the Maghreb and Sahel, the nomadic Tuareg federations chose a ...

(Chief) of the Ikazkazan

Tuareg

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym: ''Imuhaɣ/Imušaɣ/Imašeɣăn/Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group that principally inhabit the Sahara in a vast area stretching from far southwestern Libya to southern A ...

confederation, had attacked

French colonial forces

The ''Troupes coloniales'' ("Colonial Troops") or ''Armée coloniale'' ("Colonial Army"), commonly called ''La Coloniale'', were the military forces of the French colonial empire from 1900 until 1961. From 1822 to 1900 these troops were de ...

from 1909. The Sanusiya leadership in the

Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

oasis town of

Kufra

Kufra () is a basinBertarelli (1929), p. 514. and oasis group in the Kufra District of southeastern Cyrenaica in Libya. At the end of nineteenth century Kufra became the centre and holy place of the Senussi order. It also played a minor role in ...

declared

Jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

against the French colonialists in October 1914. The

Sultan of Agadez convinced the French that the Tuareg confederations remained loyal and Kaocen's forces besieged the garrison on 17 December 1916. Kaocen, his brother Mokhtar Kodogo and Tuareg raiders, armed with rifles and a field gun captured from the

Royal Italian Army

The Royal Italian Army ( it, Regio Esercito, , Royal Army) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfre ...

in

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

, defeated several French relief columns. The Tuareg seized the main towns of the Aïr, including

Ingall

Ingall is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Francis Ingall (1908–1998), British Indian Army officer

* Lisa Ingall (born 1980), English snooker player

* Marjorie Ingall (born 20th century), American non-fiction writer

* Mic ...

,

Assodé and

Aouderas

Aouderas (alt: ''Adharous'', ''Auderas'') is an oasis village in the Aïr Mountains of northeastern Niger, about north-northeast of the Regions of Niger, regional capital of Agadez. It is also the name of the valley in which the town is located ...

. Modern northern Niger came under rebel control for over three months. On 3 March 1917, a large French force from

Zinder

Zinder (locally, ''Damagaram''), formerly also spelled Sinder, is the third largest city in Niger, with a population of 170,574 (2001 census); relieved the Agadez garrison and began to recapture the towns. Mass reprisals were taken against the town populations, especially against

marabout

A marabout ( ar, مُرابِط, murābiṭ, lit=one who is attached/garrisoned) is a Muslim religious leader and teacher who historically had the function of a chaplain serving as a part of an Islamic army, notably in North Africa and the Saha ...

s, though many were neither Tuareg or rebels. The French summarily killed in public in Agadez and Ingal. Kaocen fled north; in 1919 he was killed by local militia in

Mourzouk. Kaocen's brother was killed by the French in 1920 after a revolt he led amongst the

Toubou

The Toubou or Tubu (from Old Tebu, meaning "rock people") are an ethnic group native to the Tibesti Mountains that inhabit the central Sahara in northern Chad, southern Libya and northeastern Niger. They live either as herders and nomads or as ...

and

Fula

Fula may refer to:

*Fula people (or Fulani, Fulɓe)

*Fula language (or Pulaar, Fulfulde, Fulani)

**The Fula variety known as the Pulaar language

**The Fula variety known as the Pular language

**The Fula variety known as Maasina Fulfulde

*Al-Fula ...

in the

Sultanate of Damagaram

The Sultanate of Damagaram was a Muslim pre-colonial state in what is now southeastern Niger, centered on the city of Zinder.

History

Rise

The Sultanate of Damagaram was founded in 1731 (near Mirriah, modern Niger) by Muslim Kanouri arist ...

was defeated.

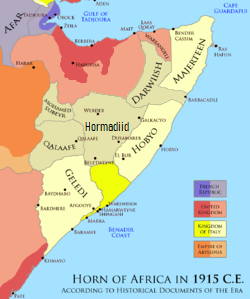

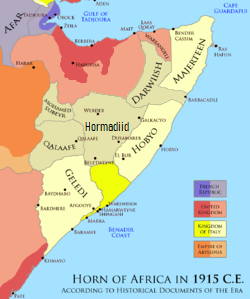

Somaliland Campaign, 1914–1918

In

British Somaliland

British Somaliland, officially the Somaliland Protectorate ( so, Dhulka Maxmiyada Soomaalida ee Biritishka), was a British Empire, British protectorate in present-day Somaliland. During its existence, the territory was bordered by Italian Soma ...

,

Diiriye Guure Diiriye may refer to:

* Diriye Osman, Somali-British writer

* Abdillahi Diiriye Guled, Somali scholar

* Diiriye Guure, king of the Darawiish sultanate

*Asha Gelle Dirie, activist for Puntite and Puntland women

*Waris Dirie Waris may refer to:

...

, sultan of the

Dervish state

The Dervish Movement ( so, Dhaqdhaqaaqa Daraawiish) was a popular movement between 1899 and 1920, which was led by the Salihiyya Sufi Muslim poet and militant leader Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, also known as Sayyid Mohamed, who called for independe ...

, continued his campaign against Ethiopian and European encroachment. In March 1914, forty Dervishes had ridden to attack

Berbera

Berbera (; so, Barbara, ar, بربرة) is the capital of the Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of the British Somaliland protectorate before Hargeisa. It ...

, the capital of British Somaliland, which caused considerable panic; in November, troops of the

Somaliland Camel Corps

The Somaliland Camel Corps (SCC) was a Rayid unit of the British Army based in British Somaliland. It lasted from the early 20th century until 1944.

Beginnings and the Dervish rebellion

In 1888, after signing successive treaties with the then r ...

, with 600 Somali and 650 Indian Army troops, captured three forts at

Shimber Berris and then had to return in February 1915 to take them again. The British adopted a policy of containment given their slender resources and tried to keep Sayyid and his 6,000 supporters penned in eastern Somaliland, to encourage desertion and ruthless killings of his own men by Sayyid, which succeeded. British prestige depended on the protection of friendly Somali areas and the deterrence of those

Somali peoples inspired by Sayyid from crossing into the

East Africa Protectorate

East Africa Protectorate (also known as British East Africa) was an area in the African Great Lakes occupying roughly the same terrain as present-day Kenya from the Indian Ocean inland to the border with Uganda in the west. Controlled by Britai ...

(British East Africa, now Kenya).

When the Ottoman Empire entered the war in November 1914, the British colonial authorities in British East Africa became apprehensive of attacks from the Muslims of Ethiopia and Somaliland but none transpired until 1916, when trouble also broke out in some Muslim units of the Indian Army stationed in East Africa, including desertions and self-inflicted wounds. In February, about 500

Aulihan

The Aulihan () are a Somali clan, a division of the Ogaden clan, living on both sides of the Kenya - Somalia border. The majorities migrated in response to pressure from the expanding Ethiopian empire and had taken control of the hinterland of th ...

warriors from Somaliland captured a British fort at Serenli and killed 65 soldiers of the garrison and their British officer. The British retired from their main fort in the north-east at

Wajir

Wajir ( so, Wajeer) is the capital of the Wajir County of Kenya. It is situated in the former North Eastern Province.

History

A cluster of cairns near Wajir are generally ascribed by the local inhabitants to the Maadiinle, a semi-legendary pe ...

and it was not for two years that the Aulihan were defeated. The complications caused by the Ottoman call to Jihad had put the British to considerable trouble in East Africa and elsewhere, to avoid the growth of a pan-Muslim movement. Even when the Ottoman call had little effect, the British were fearful of an African Jihad. To impress the Somali people, some elders were taken to Egypt in 1916 to view the military might of the British empire. The warships, railways and prison camps full of German and Ottoman soldiers made a great impression, which was increased by the outbreak of the

Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On t ...

in June.

West Africa

Togoland campaign, 1914

The Togoland Campaign (9–26 August 1914) was a

French and British invasion of the German colony of Togoland in West Africa (which became

Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

and the

Volta Region

Volta Region (or Volta) is one of Ghana's sixteen administrative regions, with Ho designated as its capital. It is located west of Republic of Togo and to the east of Lake Volta. Divided into 25 administrative districts, the region is multi-et ...

of

Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

after independence) during the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The colony was invaded on 6 August, by French forces from Dahomey to the east and on 9 August by British forces from Gold Coast to the west. German colonial forces withdrew from the capital

Lomé

Lomé is the capital and largest city of Togo. It has an urban population of 837,437 and the coastal province and then fought delaying actions on the route north to

Kamina

Kamina is the capital city of Haut-Lomami Province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Transport

Kamina is known as an important railway node; three lines of the DRC railways run from Kamina toward the north, west, and south-east. The ...

, where a new wireless station linked Berlin to Togoland, the Atlantic and South America. The main British and French force from the neighbouring colonies of Gold Coast and Dahomey advanced from the coast up the road and railway, as smaller forces converged on Kamina from the north. The German defenders were able to delay the invaders for several days at the battles of

Bafilo

Bafilo is a city in Togo south of Kara and north of Sokode in Tchaoudjo Region.

It is known for its large mosque, wagassi cheese, its weaving industry and the nearby Bafilo Falls.

History

World War I

During World War I, a skirmish took plac ...

, Agbeluvhoe and Chra but surrendered the colony on 26 August 1914. In 1916, Togoland was partitioned by the victors and in July 1922,

British Togoland

British Togoland, officially the Mandate Territory of Togoland and later officially the Trust Territory of Togoland, was a territory in West Africa, under the administration of the United Kingdom, which subsequently entered into union with Ghana ...

and

French Togoland

French Togoland (French: '' Togo français'') was a French colonial League of Nations mandate from 1916 to 1960 in French West Africa. In 1960 it became the independent Togolese Republic, and the present day nation of Togo.

Transfer from Germ ...

were created as

League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

s. The French acquisition consisted of of the colony, including the coast. The British received the smaller, less populated and less developed portion of Togoland to the west. The surrender of Togoland was the beginning of the end for the

German colonial empire

The German colonial empire (german: Deutsches Kolonialreich) constituted the overseas colonies, dependencies and territories of the German Empire. Unified in the early 1870s, the chancellor of this time period was Otto von Bismarck. Short-li ...

in Africa.

Bussa uprising, 1915

In the

Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria

Colonial Nigeria was ruled by the British Empire from the mid-nineteenth century until 1960 when Nigeria achieved independence. British influence in the region began with the prohibition of slave trade to British subjects in 1807. Britain a ...

(now Nigeria), the British policy of indirect rule through local proxies was extended after the outbreak of the First World War, when British colonial officers and troops were withdrawn for war service. The British became more dependent on local emirs but in

Bussa

Bussa's rebellion (14–16 April 1816) was the largest slave revolt in Barbadian history. The rebellion takes its name from the African-born slave, Bussa, who led the rebellion. The rebellion, which was eventually defeated by the colonial mili ...

, the re-organisation of local government in 1912 overthrew the authority of the traditional ruler. The hereditary Emir of Bussa, Kitoro Gani was moved aside and the

Borgu Emirate

The Borgu Emirate is a Nigerian traditional state with its capital in New Bussa, Niger State, Nigeria. The Emirate was formed in 1954 when the Bussa and Kaiama emirates were merged. These emirates, with Illa, were formerly part of the Borgu state, ...

was divided, each area ruled by a (native administration). In June 1915, about 600 rebels, armed with

bows and arrows

The bow and arrow is a ranged weapon system consisting of an elastic launching device (bow) and long-shafted projectiles ( arrows). Humans used bows and arrows for hunting and aggression long before recorded history, and the practice was com ...

occupied Bussa, captured and killed half of the new native administration; the survivors fled the district. The rebellion caused panic because the British authorities were so short of troops. A small force from the

West African Frontier Force

The West African Frontier Force (WAFF) was a multi-battalion field force, formed by the British Colonial Office in 1900 to garrison the West African colonies of Nigeria, Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and Gambia. In 1928, it received royal recognitio ...

(WAFF) and the

Nigeria police moved into Bussa and skirmished with the rebels. No soldiers were killed and only 150 shots were fired. Sabukki, one of the ringleaders fled to nearby

French Dahomey

French Dahomey was a French colony and part of French West Africa from 1894 to 1958. After World War II, by the establishment of the French Fourth Republic in 1947, Dahomey became part of the French Union with an increased autonomy. On 4 Octob ...

and the rebellion was suppressed.

The war in Nigeria played a role in British politics during the war. At the beginning of the war, the British government seized foreign expatriate firms in the lucrative

palm oil

Palm oil is an edible vegetable oil derived from the mesocarp (reddish pulp) of the fruit of the oil palms. The oil is used in food manufacturing, in beauty products, and as biofuel. Palm oil accounted for about 33% of global oils produced from ...

trade owned by the Central Powers. Merchants based in

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

wanted to establish a British monopoly over the trade, but the ruling

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

under Prime Minister

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

favoured allowing international competition. Although the issue was insignificant, it allowed

Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

dissatisfied with their party's exclusion from key posts and decision-making in the

Asquith coalition ministry

The Asquith coalition ministry was the Government of the United Kingdom under the Liberal Prime Minister H. H. Asquith from May 1915 to December 1916. It was formed as a multi-party war-time coalition nine months after the beginning of the Firs ...

to stage a parliamentary revolt. On November 8, 1916,

Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, PC, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician, barrister and judge, who served as the Attorney General and Solicito ...

attacked Conservative Party Leader

Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law ( ; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a ...

for supporting the Liberal position and led a successful vote against the party leadership on the issue. This began the downfall of Asquith's government and its replacement by a new

coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

of Conservatives and

Coalition Liberals led by

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, with Asquith and the majority of the Liberals going into opposition.

Kamerun campaign, 1914–1916

By 25 August 1914, British forces in Nigeria had moved into Kamerun towards Mara in the far north, towards

Garua in the centre and towards Nsanakang in the south. British forces moving towards Garua under the command of Colonel MacLear were ordered to push to the German border post at Tepe near Garua. The first engagement between British and German troops in the campaign took place at the

Battle of Tepe

The Battle of Tepe (or Tebe) on 25 August 1914 was the first skirmish between German and British forces during the Kamerun campaign in of the First World War. The conflict took place on the border between British Nigeria and German Kamerun, endi ...

, eventually resulting in German withdrawal. In the far north British forces attempted to take the German fort at Mora but failed and began a siege which lasted until the end of the campaign. British forces in the south attacked Nsanakang and were defeated and almost completely destroyed by German counterattacks at the

Battle of Nsanakong. MacLear then pushed his forces further inland towards the German stronghold of Garua but was repulsed in the

First Battle of Garua

The First Battle of Garua took place from 29 to 31 August 1914 during the Kamerun campaign of the First World War between German and invading British forces in northern Kamerun at Garua. It was the first significant action to take place in the c ...

on 31 August.

In 1915 the German forces, except for those at Mora and Garua, withdrew to the mountains near the new capital of

Jaunde. In the spring the German forces delayed or repulsed Allied attacks and a force under Captain von Crailsheim from Garua conducted an offensive into Nigeria and fought the

Battle of Gurin

The Battle of Gurin took place on 29 April 1915 during the Kamerun campaign of World War I in Gurin, British Nigeria near the border with German Kamerun. The battle was one of the largest of the German forays into the British colony. It ended in ...

. General Frederick Hugh Cunliffe began the

Second Battle of Garua

The Second Battle of Garua took place from 31 May to 10 June 1915 during the Kamerun campaign of the First World War in Garua, German Kamerun. The battle was between a combined French and British force and defending German garrison and resulte ...

in June, which was a British victory. Allied units in northern Kamerun were freed to push into the interior, where the Germans were defeated at the

Battle of Ngaundere on 29 June. Cunliffe advanced south to Jaunde but was held up by heavy rains and his force joined the

Siege of Mora. When the weather improved, Cunliffe moved further south, captured a German fort at the

Battle of Banjo

During the Battle of Banjo or Battle of Banyo, British forces besieged German forces entrenched on the Banjo mountain from 4 to 6 November 1915 during the Kamerun campaign of the First World War. By 6 November much of the German force had deser ...

on 6 November and occupied several towns by the end of the year. In December, the forces of Cunliffe and Dobell made contact and made ready to conduct an assault on Jaunde. In this year most of had been fully occupied by Belgian and French troops, who also began to prepare for an attack on Jaunde.

German forces began to cross into the Spanish colony of

Rio Muni on 23 December 1915 and with Allied forces pressing in on Jaunde from all sides, the German commander

Carl Zimmermann ordered the remaining German units and civilians to escape into Rio Muni. By mid-February, and civilians had reached Spanish territory. On 18 February the Siege of Mora ended with the surrender of the garrison. Most Kamerunians remained in Muni but the Germans eventually moved to

Fernando Po and some were allowed by Spain to travel to the

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

to go home. Some Kamerunians including the paramount chief of the

Beti people

Beti may refer to:

People

* Mongo Beti (1932–2001), Cameroonian writer

* Beti George (born 1939), Welsh television and radio broadcaster

* Beti Jones (1919–2006), Scottish social worker

* Beti Kamya-Turwomwe (born 1955), Ugandan businesswoma ...

moved to

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, where they lived as visiting nobility on German funds.

Adubi War, 1918

The Adubi War was an uprising that occurred in June and July 1918 in the British Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria, because of taxation introduced by the colonial government.

Direct tax

Although the actual definitions vary between jurisdictions, in general, a direct tax or income tax is a tax imposed upon a person or property as distinct from a tax imposed upon a transaction, which is described as an indirect tax. There is a dis ...

es were introduced by the colonial government along with existing forced labour obligations and various fees. On 7 June, the British arrested 70

Egba chiefs and issued an ultimatum that resisters should lay down their arms, pay the taxes and obey the local leaders. On 11 June, a party of soldiers returned from East Africa were brought in and on 13 July, Egba rebels pulled up railway lines at Agbesi and derailed a train. Other rebels demolished the station at Wasimi and killed the British agent and Oba Osile was attacked. Hostilities between the rebels and colonial troops continued for about three weeks at Otite, Tappona, Mokoloki and Lalako but by 10 July, the rebellion had been put down, the leaders killed or arrested. About 600 people died, including the British agent and the Oba Osile, the African leader of the north-eastern Egba district, although this may have been due to a dispute over land and unconnected to the uprising. The incident led to the abrogation of Abeokutan independence in 1918 and the introduction of

forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

in the region; imposition of the

direct taxes was postponed until 1925.

South West Africa

German South West Africa campaign, 1914–1915

An invasion of

German South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

from the south failed at the

Battle of Sandfontein

The Battle of Sandfontein was fought between the Union of South Africa on behalf of the British Imperial Government and the German Empire (modern-day Namibia) on 26 September 1914 at Sandfontein, during the first stage of the South West Afric ...

(25 September 1914), close to the border with the

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

. German fusiliers inflicted a serious defeat on the British troops and the survivors returned to British territory. The Germans began an invasion of the

Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

to forestall another invasion attempt and the

Battle of Kakamas

The battle of Kakamas took place in Kakamas, Northern Cape Province of South Africa on 4 February 1915. It was a skirmish for control of two river fords over the Orange River between contingents of a German invasion force and South African armed ...

took place on 4 February 1915, between the South African

Union Defence Force and German ''

Schutztruppe

(, Protection Force) was the official name of the colonial troops in the African territories of the German colonial empire from the late 19th century to 1918. Similar to other colonial armies, the consisted of volunteer European commissioned ...

'', a skirmish for control of two river fords over the

Orange River

The Orange River (from Afrikaans/Dutch: ''Oranjerivier'') is a river in Southern Africa. It is the longest river in South Africa. With a total length of , the Orange River Basin extends from Lesotho into South Africa and Namibia to the north ...

. The South Africans prevented the Germans from gaining control of the fords and crossing the river. By February 1915, the South Africans were ready to occupy German territory. South African Prime Minister

Louis Botha

Louis Botha (; 27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa – the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war hero during the Second Boer War, ...

put

Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

in command of the southern forces while he commanded the northern forces. Botha arrived at

Swakopmund

Swakopmund (german: Mouth of the Swakop) is a city on the coast of western Namibia, west of the Namibian capital Windhoek via the B2 main road. It is the capital of the Erongo administrative district. The town has 44,725 inhabitants and covers ...

on 11 February and continued to build up his invasion force at

Walfish Bay (or Walvis Bay), a South African enclave about halfway along the coast of German South West Africa. In March Botha began an advance from Swakopmund along the

Swakop valley with its railway line and captured

Otjimbingwe

Otjimbingwe (also: Otjimbingue) is a settlement in the Erongo Region of central Namibia. It has approximately 8,000 inhabitants.

History

The area was already a temporary settlement of some Herero in the early 18th century. Their chief Tjiponda c ...

,

Karibib

, nickname =

, settlement_type = Town

, motto =

, image_skyline =Karibib aerial view.jpg

, imagesize =300

, image_caption =Karibib aerial view 2017

, image_flag =

, ...

, Friedrichsfelde, Wilhelmsthal and

Okahandja

Okahandja is a city of 24,100 inhabitants in Otjozondjupa Region, central Namibia, and the district capital of the Okahandja electoral constituency. It is known as the ''Garden Town of Namibia''. It is located 70 km north of Windhoek on the ...

and then entered

Windhuk

Windhoek (, , ) is the capital and largest city of Namibia. It is located in central Namibia in the Khomas Highland plateau area, at around above sea level, almost exactly at the country's geographical centre. The population of Windhoek in 202 ...

on 5 May 1915.

The Germans offered surrender terms, which were rejected by Botha and the war continued. On 12 May Botha declared martial law and divided his forces into four contingents, which cut off German forces in the interior from the coastal regions of

Kunene and

Kaokoveld

The Kaokoveld Desert is a coastal desert of northern Namibia and southern Angola.

Setting

The Kaokoveld Desert occupies a coastal strip covering , from 13° to 21°S and is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Namibian savanna woodl ...

and fanned out into the north-east. Lukin went along the railway line from Swakopmund to

Tsumeb

, nickname =

, settlement_type = City

, motto = ''Glück Auf'' (German language, German for ''Good luck'')

, image_skyline = Welcome to tsumeb.jpg

, imagesize =

, image_caption ...

. The other two columns rapidly advanced on the right flank, Myburgh to

Otavi

Otavi is a town of 4,000 inhabitants in the Otjozondjupa Region of central Namibia. Situated 360 km north of Windhoek, it is the district capital of the Otavi electoral constituency.

Geography

The towns of Otavi, Tsumeb (to the north) and Gro ...

junction and Manie Botha to Tsumeb and the terminus of the railway. German forces in the north-west fought the

Battle of Otavi

The Battle of Otavi fought between the militaries of the Union of South Africa and German Southwest Africa on 1 July 1915 was the final battle of the South West Africa Campaign of World War I. The battle, fought between Otavi mountain and Otavifo ...

on 1 July but were defeated and surrendered at

Khorab on 9 July 1915. In the south, Smuts landed at the South West African naval base at

Luderitzbucht, then advanced inland and captured

Keetmanshoop

Keetmanshoop is a city in the ǁKaras Region of southern Namibia, lying on the Trans-Namib Railway from Windhoek to Upington in South Africa. It is named after Johann Keetman, a German industrialist and benefactor of the city.

History

Befo ...

on 20 May. The South Africans linked with two columns which had advanced over the border from South Africa. Smuts advanced north along the railway line to

Berseba

Berseba ( Nama: ǃAutsawises) is a village in the ǁKaras Region of southern Namibia and the district capital of the Berseba electoral constituency. It is situated north-west of Keetmanshoop near the Brukkaros Mountain, a famous tourist des ...

and on 26 May, after two days' fighting captured

Gibeon. The Germans in the south were forced to retreat northwards towards Windhuk and Botha's force. On 9 July the German forces in the south surrendered.

Maritz rebellion, 1914–1915

General

Koos de la Rey

Jacobus Herculaas de la Rey (22 October 1847 – 15 September 1914), better known as Koos de la Rey, was a South African military officer who served as a Boer general during the Second Boer War. also had a political career and was one of the l ...

, under the influence of

Siener van Rensburg

Nicolaas Pieter Johannes ("Niklaas" or "Siener") Janse van Rensburg (3 August 1864 – 11 March 1926) was a Boer from the South African Republic – also known as the Transvaal Republic – and later a citizen of South Africa who was consid ...

, a "crazed seer", believed that the outbreak of war foreshadowed the return of the republic but was persuaded by Botha and Smuts on 13 August not to rebel and on 15 August told his supporters to disperse. At a congress on 26 August, De la Rey claimed loyalty to South Africa, not Britain or Germany. The Commandant-General of the Union Defence Force, Brigadier-General

Christian Frederick Beyers

Christiaan Frederik Beyers (23 September 1869 – 8 December 1914) was a Boer general during the Second Boer War.

Biography

As a young man, he went to the South African Republic, Transvaal, where he took a prominent part on the Boer side in the ...

, opposed the war and with the other rebels, resigned his commission on 15 September. General Koos de la Rey joined Beyers and on 15 September they visited Major

Jan Kemp Jan Kemp may refer to:

*Jan Kemp (general)

Jan Christoffel Greyling Kemp (10 June 1872 – 31 December 1946) was a South African Boer officer, rebel general, and politician.

Early life

Jan Kemp was born in the present Amersfoort district, Tra ...

in

Potchefstroom

Potchefstroom (, colloquially known as Potch) is an academic city in the North West Province of South Africa. It hosts the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University. Potchefstroom is on the Mooi Rivier (Afrikaans for "pretty river" ...

, who had a large armoury and a force of many of whom were thought to be sympathetic. The South African government believed it to be an attempt to instigate a rebellion. Beyers claimed that it was to discuss plans for a simultaneous resignation of leading army officers, similar to the

Curragh incident

The Curragh incident of 20 March 1914, sometimes known as the Curragh mutiny, occurred in the Curragh, County Kildare, Ireland. The Curragh Camp was then the main base for the British Army in Ireland, which at the time still formed part of the U ...

in Ireland.

During the afternoon De la Rey was mistakenly shot and killed by a policeman, at a roadblock set up to look for the

Foster gang; many Afrikaners believed that De la Rey had been assassinated. After the funeral, the rebels condemned the war but when Botha asked them to volunteer for military service in South West Africa they accepted.

Manie Maritz, at the head of a commando of Union forces on the border of German South West Africa, allied with the Germans on 7 October and issued a proclamation on behalf of a provisional government and declared war on the British on 9 October. Generals Beyers,

De Wet De Wet is the name of:

* Jacob Willemszoon de Wet (c. 1610 – between 1675 and 1691), Dutch painter

* Christiaan de Wet (1854–1922), Boer general, rebel leader and politician

** De Wet Decoration, South African military medal named after the ab ...

, Maritz, Kemp and Bezuidenhout were to be the first leaders of a new

South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

. Maritz occupied

Keimoes

Keimoes is a town in the Northern Cape province of South Africa. It lies on the Orange River and is about halfway between Upington and Kakamas.

History

It attained municipal status in 1949. The name of the town translates in both the Khoekhoe and ...

in the Upington area. The

Lydenburg

Lydenburg, officially known as Mashishing, is a town in Thaba Chweu Local Municipality, on the Mpumalanga highveld, South Africa. It is situated on the Sterkspruit/Dorps River tributary of the Lepelle River at the summit of the Long Tom Pass. ...

commando under General De Wet took possession of the town of

Heilbron

Heilbron is a small farming town in the Free State province of South Africa which services the cattle, dairy, sorghum, sunflower and maize industries. Raw stock beneficiation occurs in leisure foods, dairy products and stock feeds. It also se ...

, held up a train and captured government stores and ammunition.

By the end of the week, De Wet had a force of and Beyers had gathered more in the

Magaliesberg

The Magaliesberg (historically also known as ''Macalisberg'' or ''Cashan Mountains'') of northern South Africa, is a modest but well-defined mountain range composed mainly of quartzites. It rises at a point south of the Pilanesberg (and the Pil ...

. General Louis Botha had pro-government troops. The government declared martial law on 12 October and loyalists under General Louis Botha and Jan Smuts repressed the uprising. Maritz was defeated on 24 October and took refuge with the Germans; the Beyers commando force was dispersed at

Commissioners Drift

A commissioner (commonly abbreviated as Comm'r) is, in principle, a member of a Regulatory agency, commission or an individual who has been given a Wiktionary: commission, commission (official charge or authority to do something).

In practice, th ...

on 28 October, after which Beyers joined forces with Kemp and then was drowned in the

Vaal River

The Vaal River ( ; Khoemana: ) is the largest tributary of the Orange River in South Africa. The river has its source near Breyten in Mpumalanga province, east of Johannesburg and about north of Ermelo and only about from the Indian Ocean. ...

on 8 December. De Wet was captured in

Bechuanaland on 2 December and Kemp, having crossed the

Kalahari desert

The Kalahari Desert is a large semi-arid sandy savanna in Southern Africa extending for , covering much of Botswana, and parts of Namibia and South Africa.

It is not to be confused with the Angolan, Namibian, and South African Namib coastal de ...

and lost and most of their horses on the journey, joined Maritz in German South West Africa and attacked across the Orange River on 22 December. Maritz advanced south again on 13 January 1915 and with German support attacked Upington on 24 January but was repulsed. Most of the rebels then surrendered on 30 January.

German invasion of Angola, 1914–1915

The campaign in southern

Portuguese West Africa

Portuguese Angola refers to Angola during the historic period when it was a territory under Portuguese rule in southwestern Africa. In the same context, it was known until 1951 as Portuguese West Africa (officially the State of West Africa).

I ...

(modern-day

Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

) took place from Portuguese forces in southern Angola were reinforced by a military expedition led by Lieutenant-Colonel

Alves Roçadas, which arrived at Namibe, Moçâmedes on 1 October 1914. After the loss of the wireless transmitter at Kamina in Togoland, German forces in South West Africa could not communicate easily and until July 1915 the Germans did not know if Germany and Portugal were at war (war was declared by Germany on 9 March 1916.). On 19 October 1914, an incident occurred in which fifteen Germans entered Angola without permission and were arrested at fort Naulila and in a mêlée three Germans were killed by Portuguese troops. On 31 October, German troops armed with machine guns launched a surprise attack, which became known as the ''Cuangar Massacre'', on the small Portuguese Army outpost at Cuangar and killed eight soldiers and a civilian.

On 18 December a German force of under the command of Major Victor Franke attacked Portuguese forces at Naulila. A German shell detonated the munitions magazine at Forte Roçadas and the Portuguese were forced to withdraw from the Ovambo region to Humbe, with and taken prisoner. The Germans lost killed and Local civilians collected Portuguese weapons and rose against the colonial regime. On 7 July 1915, Portuguese forces under the command of General Pereira d'Eça reoccupied the Humbe region and conducted a reign of terror against the population. The Germans retired to the south with the northern border secure during the Ovambo Uprising, which distracted Portuguese forces from operations further south. Two days later German forces in South West Africa surrendered, ending the South West Africa Campaign.

East Africa

East African campaign, 1914–1915

Military operations, 1914–1915

On the outbreak of war there and in the King's African Rifles in East Africa. On 5 August 1914, British troops from the Uganda Protectorate attacked German outposts near Lake Victoria and on 8 August and bombarded Dar es Salaam. On 15 August, German forces in the Neu Moshi region captured Taveta, Kenya, Taveta on the British side of Mount Kilimanjaro. In September, the Germans raided deeper into Kenya, British East Africa and Uganda and operations were conducted on Lake Victoria by a German boat armed with a QF 1 pounder pom-pom gun. The British armed the Uganda Railway lake steamers , , and and regained command of Lake Victoria, when two of the British boats trapped the tug, which was then scuttled by the crew. The Germans later raised the tug, salvaged the gun and used the boat as a transport.

The British command planned an operation to suppress German raiding and to capture the northern region of the German colony. Indian Expeditionary Force, Indian Expeditionary Force B of in two brigades would land at Tanga, Tanzania, Tanga on 2 November 1914 to capture the city and take control the Indian Ocean terminus of the Usambara Railway. Near Kilimanjaro, Indian Expeditionary Force C of in one brigade, would advance from British East Africa on Neu-Moshi on 3 November, to the western terminus of the railway. After capturing Tanga, Force B would rapidly move north-west to join Force C and mop up the remaining Germans. Although outnumbered and Battle of Kilimanjaro, Longido, the under Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck defeated the British offensive. In the United Kingdom's official ''History of the Great War'', Charles Hordern wrote that the operation was "... one [of] the most notable failures in British military history".

Chilembwe uprising, 1915

The uprising was led by John Chilembwe, a Millenarianism, millenarian Christian minister of the Watch Tower Society, Watch-Tower Society, in the Chiradzulu district of Nyasaland (now Malawi) against colonial forced labour, racial discrimination and new demands on the population caused by the outbreak of World War I. Chilembwe rejected co-operation with Europeans in their war, when they withheld property and human rights from Africans. The revolt began in the evening of 23 January 1915, when rebels attacked a plantation and killed three colonists. In another attack early in the morning of 24 January in Blantyre, several weapons were captured. News of the insurrection was received by the colonial government on 24 January, which mobilised the settler militia and two companies of the King's African Rifles from Karonga. The soldiers and militia attacked Mbombwe on 25 January and were repulsed. The rebels later attacked a nearby Christian mission and during the night fled from Mbombwe to Portuguese East Africa. On 26 January government forces took Mbombwe unopposed and Chilembwe was later killed by a police patrol, near the border with Portuguese East African border. In the repression after the rebellion, more than were killed and were imprisoned.

Naval operations, 1914–1916

Battle of the Rufiji Delta, 1915

A light cruiser, of the Imperial German Navy, was in the Indian Ocean when war was declared. ''Königsberg'' sank the cruiser HMS ''Pegasus'' in Zanzibar City harbour and then retired into the Rufiji River delta. After being cornered by warships of the British Cape Squadron, two Monitor (warship), monitors, and , armed with guns, were towed to the Rufiji from British Malta, Malta by the Red Sea and arrived in June 1915. On 6 July, clad in extra armour and covered by a bombardment from the fleet, the monitors entered the river. The ships were engaged by shore-based weapons hidden among trees and undergrowth. Two aircraft based at Mafia Island observed the fall of shells, during an exchange of fire at a range of with ''Königsberg'', which had assistance from shore-based spotters.

''Mersey'' was hit twice, six crew killed and its gun disabled; ''Severn'' was straddled but hit ''Königsberg'' several times, before the spotter aircraft returned to base. An observation party was seen in a tree and killed and when a second aircraft arrived both monitors resumed fire. German return fire diminished in quantity and accuracy and later in the afternoon the British ships withdrew. The monitors returned on 11 June and hit ''Königsberg'' with the eighth salvo and within ten minutes the German ship could only reply with three guns. A large explosion was seen at At seven explosions occurred. By ''Königsberg'' was a mass of flames. The British salvaged six guns from the ''Pegasus'', which became known as the ''Peggy guns'', and the crew of ''Königsberg'' salvaged the main battery guns of their ship and joined the .

Lake Tanganyika expedition, 1915